Everything You Need to Know About Women in Ancient Egypt

When we consider the role of women in ancient societies, the assumption is often that they were treated as second class citizens. However, while Ancient Egypt was undoubtedly a patriarchy – that is, a society based on the principle of men in power – there was also a surprising amount of gender equality. In fact, women were legally, spiritually, and socially regarded in such high standing that there is much modern societies could learn from the example set by the Ancient Egyptians. Let’s take a look at exactly what life was like for women in one of the greatest civilizations of all time.

A Pantheon of Female Goddesses

The respect with which women were treated in Ancient Egypt had its basis in religion. For the Ancient Egyptians, balance and equality were intrinsic to their belief system – as were feminine concepts such as fertility and rebirth. The Egyptian pantheon included many, many female deities, each with a different area of expertise. These ranged from the everyday (like brewing beer and watching over pregnancies) to the divine (like protecting humanity from evil). Some of the most important deities were female – including Neith, an early goddess often cited as the primary creator in tales of how the world was made; and Isis, sister, wife, and equal of Osiris and the deity in charge of shepherding the deceased safely into the afterlife. Both Hathor and Isis were at different points considered the divine mother of the pharaoh and worshipped extensively with their own special cults.

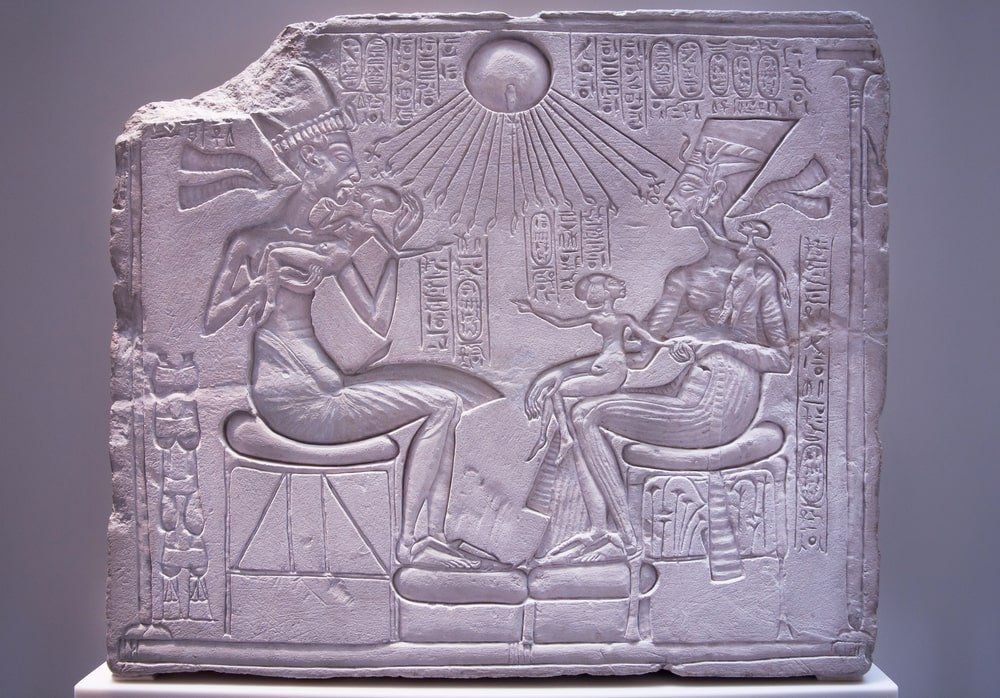

Women in Positions of Power

It wasn’t only divine females that possessed great power in Ancient Egypt. Mortal women also shaped the country’s history – usually as the influential wife or mother of the pharaoh but also sometimes in their own right.

Sobekneferu

Sobekneferu was not the first female ruler of Ancient Egypt; at least one, Meritneith, is thought to have ruled as regent in place of her son as early as the First Dynasty. However, she was the first woman known to have assumed the full title of pharaoh, which she did after the death of Amenemhat IV (who was probably both her husband and her brother). She was the last ruler of the Twelfth Dynasty, and is thought to have held power for almost four years.

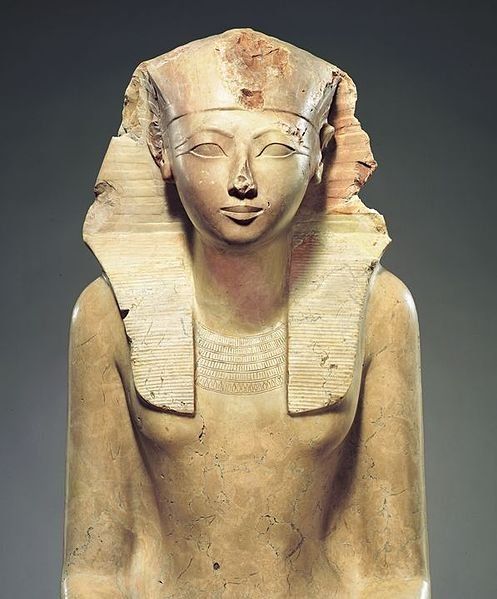

Hatshepsut

The next confirmed female pharaoh was Hatshepsut, who ruled for approximately 22 years during the Eighteenth Dynasty – first as regent to her stepson, Thutmose III, but later in her own right. She is renowned as one of the most powerful and successful Egyptian rulers of all time. Her achievements included re-establishing valuable trade routes suspended during the occupation of the Hyskos; a lucrative expedition to the Land of Punt; military campaigns against Nubia and Canaan; and one of the most ambitious building projects the kingdom had ever seen.

Cleopatra VII

Probably the most famous female pharaoh, Cleopatra VII was the last ruler of the Ptolemaic Dynasty. As a highly ambitious stateswoman and later as consort of both Julius Caesar and Mark Antony, she earned a reputation both in her own time and ever since as one of the most powerful, accomplished, and beautiful women of all time.

Rights for Everyday Women

Of course, life for non-royal women would have been very different; nevertheless, many historians believe that men and women were given almost equal standing in Ancient Egypt. Legally, women had many more rights than their counterparts in some modern societies. The line of inheritance was matrilineal, which meant that property and wealth was handed down from mother to daughter rather than from father to son. This was presumably because maternity (unlike paternity) could never be questioned. This meant that women could not only inherit assets, but they could have their own will and bequeath it as they chose.

During their own lifetime, they could both administer and dispose of property as they wished. Women could own and run an estate or business even after getting married – in fact, while most tended to fulfil traditional household roles, there was no law to prevent them from pursuing all kinds of professions. Possible occupations included scribe, priestess (usually in a temple dedicated to a female deity), teacher, weaver, dancer, musician, and even physician. Lower class women typically worked alongside their husbands in the fields. There were a few jobs that women would not have held – these included administrator and civil servant.

In terms of the law, a woman could serve as a an executor for wills, witness legal documents, sit on a jury, adopt children, and bring cases to court. She could even defend herself in court; which may have been necessary, because women could be sued and tried just like men (although punishments often differed).

Relationships, Marriage, and Divorce

Girls typically married young in Ancient Egypt – usually between the ages of 12 and 14. Husbands were often chosen by their families; however, women could not be forced to marry someone and had the right to refuse a proposal. While polygamy was common for pharaohs and not unusual for wealthy members of the elite, getting married was expensive and the vast majority of marriages would have been monogamous. Women were expected to fulfil traditional marital and maternal duties in addition to any occupation they chose to have. This meant preparing meals, brewing beer (water was rarely drinkable in Ancient Egypt), caring for children, keeping the house clean, and laundering clothes in the river. Of course, wealthy women would have supervised these roles rather than performing them themselves.

That’s not to say that divorce didn’t happen – in fact, it was relatively common and could be initiated by either partner. Before marrying, couples would enter a prenuptial agreement, and this typically favored the wife. If the husband asked for a divorce, he could not claim any property from the marriage and would have to pay maintenance for his wife and children. In either case, the wife was always given full custody, her original dowry, and any assets earned or inherited in her own name during the marriage. Unless previously owned by the husband’s family, she would also have been granted the marital home. Adultery was illegal for both partners. The most common punishment for unfaithful wives was to have their noses slit – a form of disfigurement chosen both because it was humiliating and because it was impossible to hide.

Pregnancy, Birth, and Motherhood

The main purpose of marriage in Ancient Egypt was to produce an heir. In fact, infertility was one of the most common reasons for a man to divorce his wife. The Egyptians were so preoccupied with fertility that they are credited with one of the earliest pregnancy tests. A woman who suspected she was with child would urinate into a cloth bag that held both wheat and barley grains. If either plant germinated, the woman was pregnant. If the wheat grew first, the child would be female, and if the barley grew first, it would be male. As an indicator of pregnancy, this test was actually fairly accurate: Modern studies have shown it to be successful in identifying between 70 and 85% of pregnancies.

Childbirth was a dangerous prospect for Ancient Egyptian women, with no real medical assistance available in the event of a problem. Instead, the woman would have been attended by female members of her family, who would have used amulets and religious statues to invoke the protection of various goddesses. There was a standard birthing position, too – women would have been helped to squat over a mat kept in place by four bricks, each of which was meant to represent a different goddess.

Women went through this process many times, with the average family having between four and six children (and often many more). That’s not to say all of these babies survived to adulthood. Rates of infant mortality were high, especially given the prevalence of tropical diseases and infection. Babies who did survive were carried around in a sling, and breastfed for up to three years. Lower class girls were usually taught life skills by their mothers rather than given a formal education. However, upper class girls were often taught to read and write and about subjects such as history and politics. This would have been in preparation for them to run the family business, or to make a suitable wife for a powerful husband.

Women who were not ready to have children had options in Ancient Egypt, with many different forms of birth control cited in various medical papyruses. Two of the most popular included seed-wood soaked in ground acacia leaves and honey, and crocodile dung mixed with sour milk. Both concoctions would have been inserted into the vagina to act as a sperm barrier, and are likely to have been at least somewhat effective due to their acidic nature. Abortions were documented, too, made possible by the drinking of herbal concoctions or the use of vaginal douches and suppositories.

Personal Hygiene

Cleanliness was of sacred importance to all Ancient Egyptians, regardless of class or gender. As such, women would have bathed almost daily – either in the River Nile, or if they could afford it, in the privacy of their own homes in tubs filled by their slaves. By the time the New Kingdom dawned, bath houses became popular. They had separate sections for each gender and the water would have been supplied by slaves (running water only came with the arrival of the Romans). The most common soap was natron, or soda ash mixed with oil. In its undiluted form it could also be used as a kind of toothpaste. For the elite, cleaning rituals would have involved animal fat, perfume, oil, scrubbing salts, and (as made famous by Cleopatra) milk.

The Ancient Egyptians even had their own version of deodorant. Instead of being applied under the arms, however, it took the form of a cone of perfumed wax placed on top of their heads at social events. The wearer’s body heat would cause the wax to melt over time, releasing a pleasant fragrance to mask any unwanted odors. Women who were menstruating would have been considered impure and excused from activities that had the potential to contaminate other family members, such as cooking. Certain sections of the temple would also have been off limits to women at this time. The Ancient Egyptians were a resourceful bunch, developing the first known form of tampon from softened, rolled up papyrus.

Fashion in Ancient Egypt

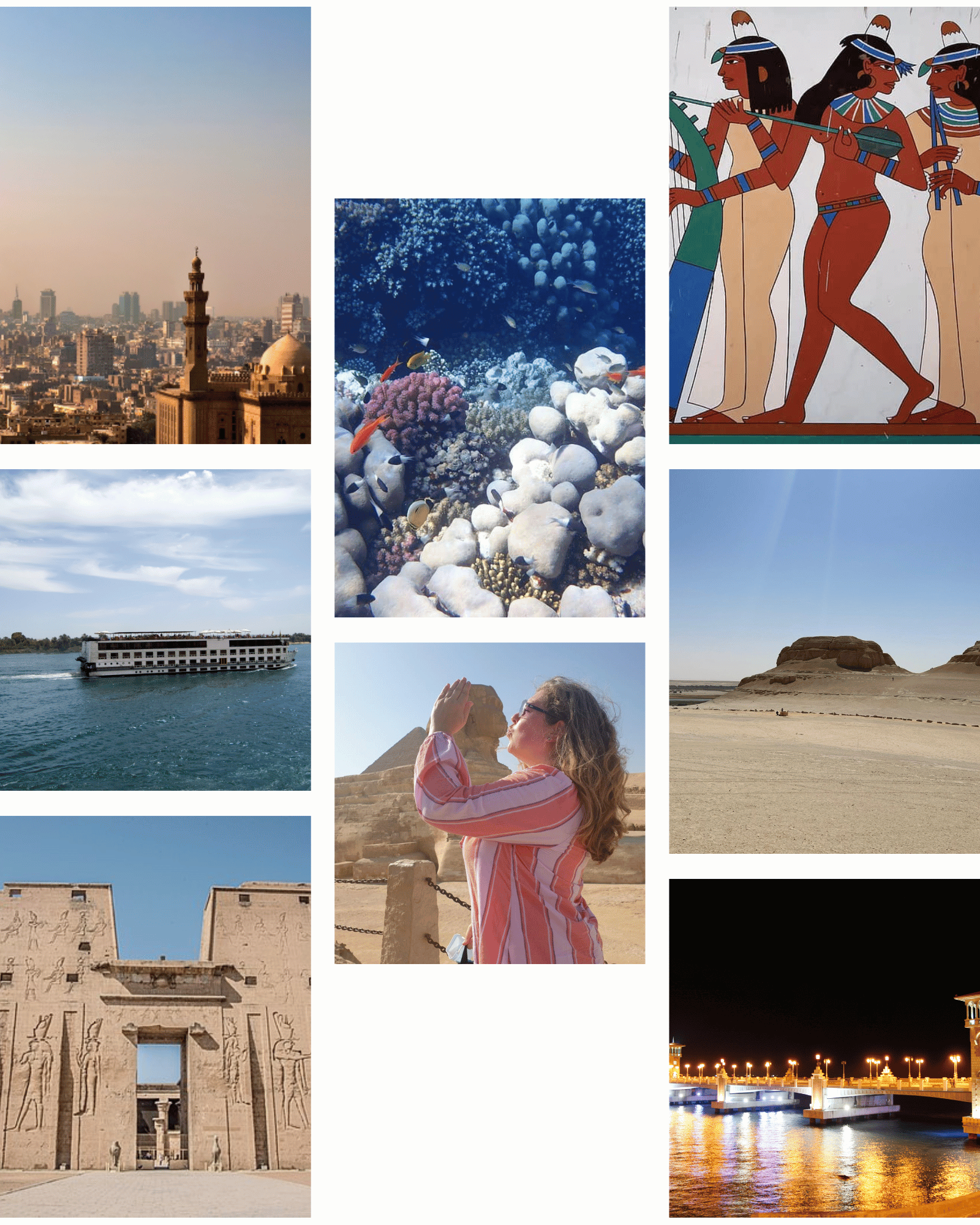

So, once they were freshly bathed, what would Ancient Egyptian women have worn? While few garments have survived intact from the time of pharaohs, the many reliefs and paintings found on the walls of ancient monuments and tombs tell us that although precise styles varied depending on class and era, the basics remained the same. Flax was woven into a light, cool fabric that provided efficient protection from the sun; and while it was typically kept white, it could also be rendered in shades such as red, blue, and yellow with the help of natural dyes. For servants and working class women, close-fitting, ankle-length sheath dresses were the most practical style.

Wealthy women and royalty had similar garments, albeit embellished with pleating, beadwork, and gold thread. Later, a transparent wrap or shawl would have been added as a further symbol of wealth; and eventually, off-the-shoulder styles crept into fashion as a result of Greek and Roman influences. Generally, most Egyptian women would have gone barefoot. However, there is evidence that the wealthier classes also fashioned sandals from leather and papyrus.

Hair was worn loose and long by the lower classes, who sometimes used henna to produce a lighter color. It was common for elite men and women to shave their heads and wear elaborate wigs instead. For the wealthiest, these would have been made out of human hair; more affordable versions were padded with or made entirely out of plant fibers. Both sexes also wore makeup. Kohl was used heavily around the eyes, both to beautify and as protection from the harsh glare of the sun. Eye shadow was created used ground malachite (green) and galena (dark grey), while red ochre was mixed with oil or fat to be applied as rouge and/or lipstick. Makeup applicators, mirrors, and perfume containers have all been found in Ancient Egyptian tombs.

Finally, women of all classes would have worn jewelry. This also served a double purpose – as adornment, and for the incorporation of talismans to protect the wearer from evil spirits. From armbands to anklets, necklaces, bracelets, rings, and amulets, jewelry often featured the same popular symbols over and over again. These included the ankh (symbol of life), the scarab (symbol of rebirth), and the Shen ring (for eternal protection). While wealthy women’s jewelry was crafted from precious stones and metals, that of the working class was made from pottery and inlaid with reflective glass or faience.