Everything You Need to Know About the Great Pyramid of Giza

The Great Pyramid of Giza goes by many names – to some, it’s the Pyramid of Khufu or the Pyramid of Cheops – but whatever you call it, is is undoubtedly the single most iconic ancient sight in all of Egypt. Visitors have been enthralled by the pyramid since ancient times, partly because it is the oldest and the largest of the three Giza pyramid complexes; and partly because it is still shrouded in mystery. Even today, questions like how and why it was built, what purpose its internal passageways and chambers served, and who was the first to enter the pyramid after it was sealed still remain largely unanswered.

Incredible Statistics

Built over 4,500 years ago, the Great Pyramid of Giza is the oldest of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. It is also the only one that survives today – a testament to the incredible architectural and engineering skills of the Ancient Egyptians. In its heyday the pyramid stood 146.5 metres tall. It was the world’s tallest man-made structure for more than 3,800 years, until that title was usurped by Lincoln Cathedral in 1311 AD. It is comprised of around 2.3 million blocks of limestone and granite, together weighing in at around 6 million tonnes. And although many of these blocks came from local quarries, the largest were transported some 800 kilometres along the River Nile from Aswan.

It is not just the pyramid’s sheer scale that makes it special. It is also the incredible precision with which it was built, at a time when most of the tools modern engineers rely on didn’t exist. Each of its four bases were completed with such accuracy that there is an average error of just 0.58 centimetres between their lengths.

Construction and Layout

Construction

The Great Pyramid of Giza is believed to have been commissioned by the Fourth Dynasty pharaoh Khufu (known to the Greeks as Cheops) to serve as a monumental tomb. Its construction took between 10 and 20 years, with experts estimating it to have been completed in around 2560 BC. Up until relatively recently, historians believed that the pyramid was the result of slave labour. However, the discovery of nearby workers’ villages and the precision with which the structure was made suggests that it was actually built by teams of paid skilled workers. During peak construction periods, as many as 40,000 people could have worked on the pyramid at any one time.

The most likely quarrying technique involved hammering wooden wedges into the grooves of natural rock faces, then soaking them with water so that the wedges expanded and broke off chunks that could then be carved by hand into blocks. These blocks would then have been transported to the River Nile and sailed up or downriver to the building site; although debate continues as to how they were manoeuvred into place at the other end. The largest of the blocks weighed up to 80 tonnes each.

Originally, the pyramid would have been encased in blocks of smooth, white limestone. These blocks were removed for the building projects of medieval sultans, leaving the beige-coloured core structure we’re familiar with today. Some of the white limestone blocks can still be seen at the Giza site, lying where they fell after being loosened by an earthquake in 1303.

Layout

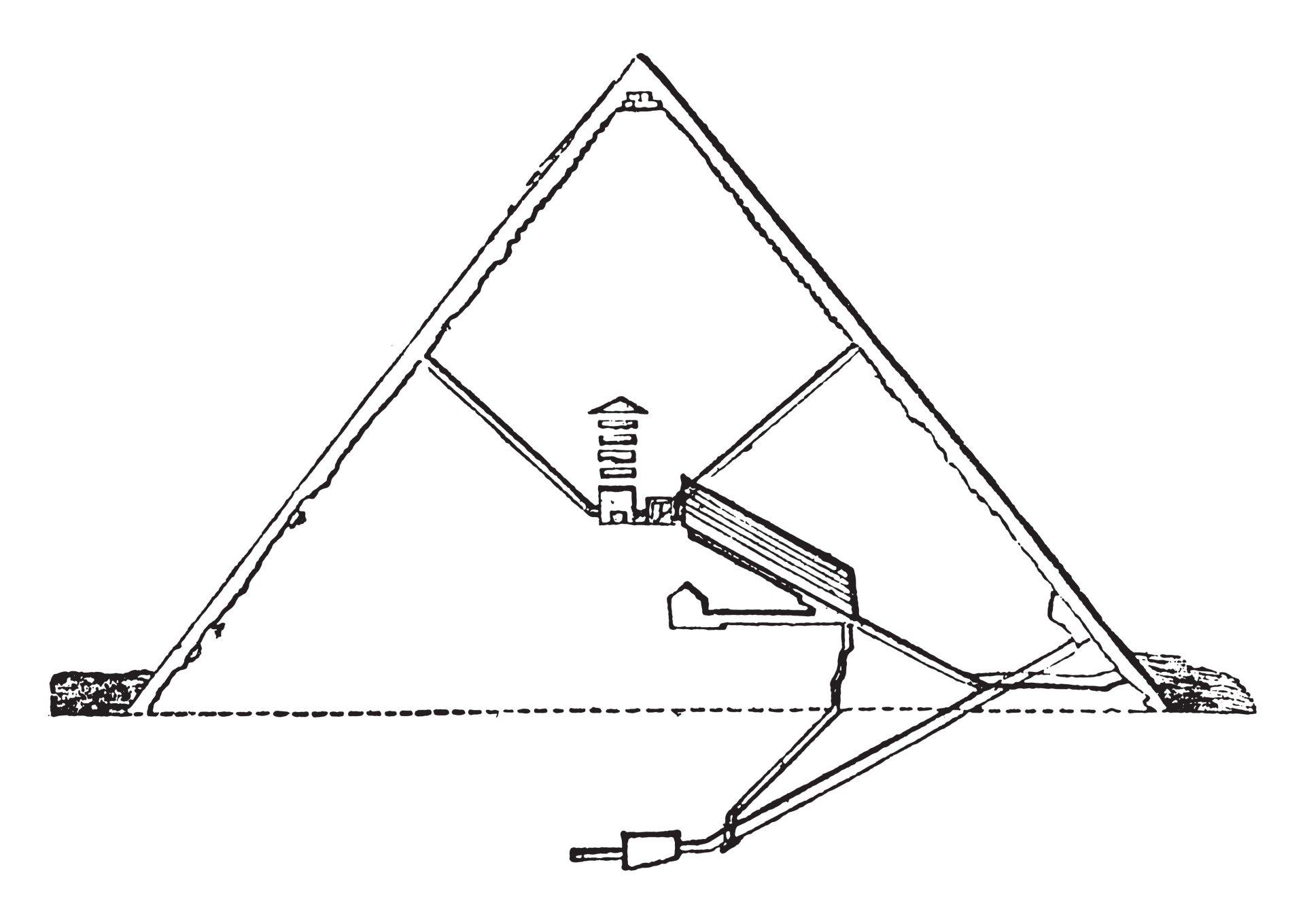

Khufu’s pyramid is unique in that it is the only one of all those built between 2630 and 1750 BC to include internal passages and chambers in the main body of the structure. These are accessed via an entrance in the pyramid’s north face, carved 17 metres above ground level. From there the Descending Passage leads downwards through the bedrock to the Subterranean Chamber, which was never finished. It is unclear whether the chamber was abandoned because the pharaoh changed his mind about building plans half way through; or whether it served a purpose that we have not yet determined.

28 metres from the original entrance, a square-shaped hole in the roof leads up into the Ascending Passage. This hole was initially disguised by granite plugs, probably to confuse potential grave robbers. The passage leads upwards at almost exactly the same angle as the Descending Passage, linking to the Great Gallery where smaller horizontal passages at the top and bottom lead to the King’s Chamber and the Queen’s Chamber respectively.

From the King’s Chamber, two narrow shafts lead upwards to the pyramid’s exterior. Their purpose is not clear, although theories suggest that they were either for ventilation or to allow the king’s spirit to ascend to the heavens. Similar shafts lead upwards from the Queen’s Chamber as well, although these end abruptly within the rock at miniature doors complete with copper handles – yet another of the pyramid’s unexplained mysteries. Above the King’s Chamber are five small Relieving Compartments, believed to have been built to reduce the pressure of the rock and stop it from caving in. The pharaoh’s granite sarcophagus remains inside the chamber.

Discovery and Excavation

The history of the pyramid’s discovery is complicated. The Descending Passage was opened in antiquity, probably not long after the pyramid was first sealed. Certainly it was known to the historians of Green and Roman times. These same historians make no mention of the Ascending Passage, however, which suggests that it remained undetected until the explorations of Muslim Caliph Ma’mun in the 9th century. Unable to find the original entrance, the caliph’s men dug their own way into the pyramid and dislodged the concealing granite plug in the process.

However, when they reached the King’s Chamber, legend has it that they found Khufu’s mummy and the treasures with which he was presumably buried missing – suggesting that some unknown person had already found their way into the chamber.

The pyramid was first excavated using modern techniques by British Egyptologist Sir Flinders Petrie in 1880. Petrie took the first precision measurements of the pyramid and much of what we know about its dimensions are based on his findings. Ever since, explorations of the pyramid have continued, sometimes answering questions and often raising new ones. In 2017, scientists from the ScanPyramids project used muon radiography to reveal a previously undiscovered void located directly above the Great Gallery. As yet it is still not accessible and its purpose is unknown, proving that the pyramid still keeps some secrets over 4,500 years later.

Visiting the Pyramid Today

Today, the pyramid stands almost as proud and tall as it did when it was first built; although without the limestone casing, its height has been reduced to 137 metres. Visitors can admire its world-famous silhouette from the outside, or venture inside to the Great Gallery and both royal chambers. Public access to the Subterranean Chamber is usually not allowed. The passages are tight at just under a metre in height and just over a metre in width. They’re also steep, so you need to be relatively fit and able to deal with confined spaces to enter them. Those that do will have the incredible experience of travelling quite literally through over four thousand years of history.

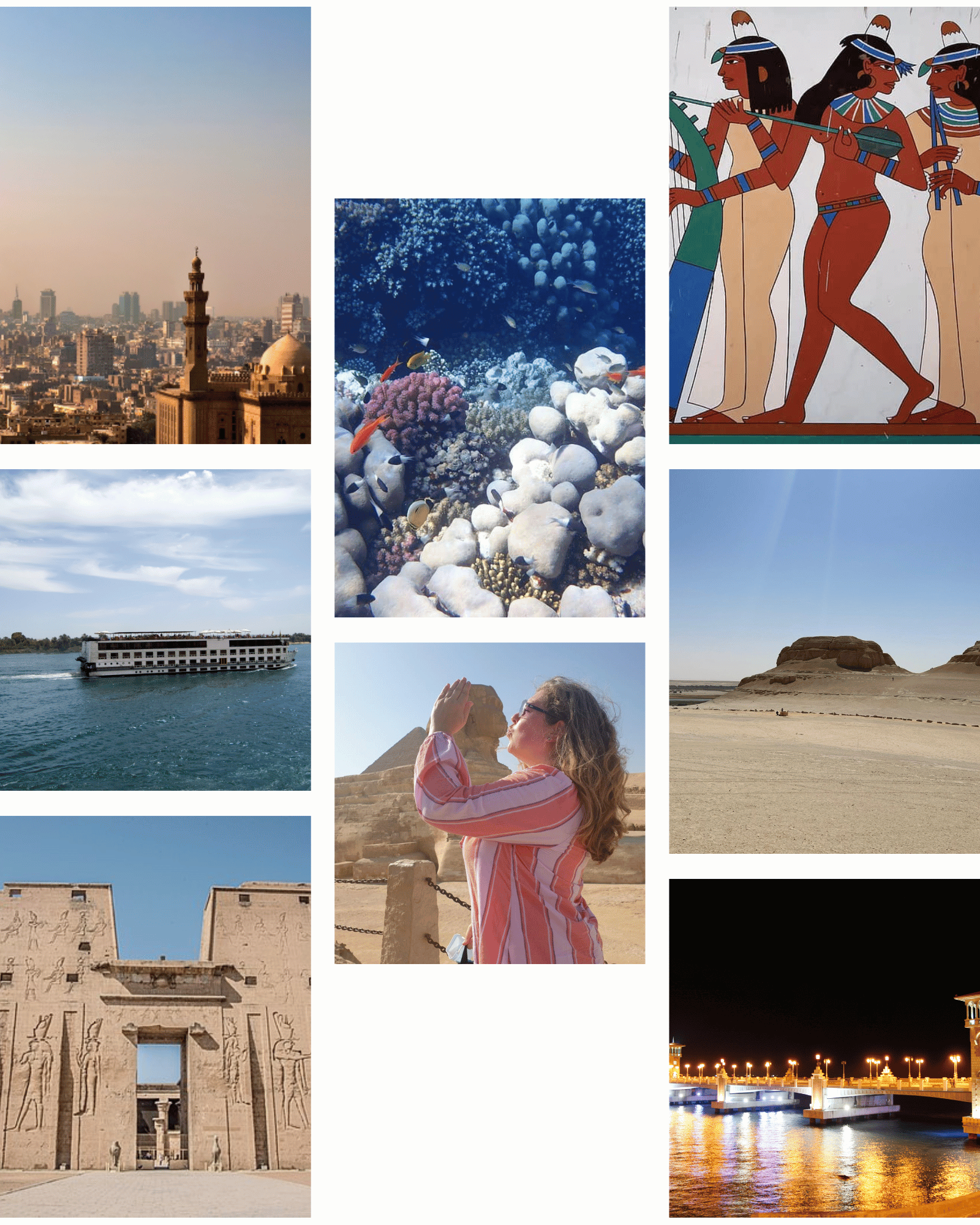

There is more to the complex than the Great Pyramid itself, although it is undoubtedly the star attraction. It also includes several other, smaller pyramids that belonged to Khufu’s wives and sisters, two temples, and the mastaba tombs of respected nobles. Also of interest are the solar barque pits in which the pharaoh’s ritual boats would have been buried. In 1954, an unopened boat pit was discovered with 1,224 pieces of wood inside. These were restored and reassembled using traditional methods, and the barque can now be seen at the on-site Solar Boat Museum.

The Giza site also includes the pyramid complexes of Khafre (Khufu’s son) and Menkaure; as well as the Giant Sphinx of Giza. It is possible to visit the pyramids independently. However, there is so much to see, and so many stories, hypotheses and mysteries to uncover, that it is more rewarding to go with an experienced Egyptologist guide. At Pyramids Land Tours, we offer a range of guided excursions to suit every kind of traveller. These range from luxury private tours of the entire Giza site to full-day tours that combine the pyramids with a visit to some of Cairo’s top attractions. If you’re particularly passionate about pyramids, you can even join a two-day tour that visits the structures at Saqqara and Dahshur as well.