Ancient Egyptian History

Ancient Egyptian History, From Prehistory to the Roman Era

Ancient Egyptian history began with the first prehistoric people to settle in the Nile Valley and ended with the annexing of Egypt to the Roman Empire in 30 BC. Within this timeframe was the pharaonic period, a civilisation that lasted from the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt in the 32nd century BC and only ended when Alexander the Great assumed rulership of the country in 332 BC. Ancient Egypt in the time of the pharaohs has since become known as one of the most influential civilisations the world has ever seen. Many achievements from that period remain a source of wonder for modern historians and have shaped the way we live today.

Prehistoric Egypt

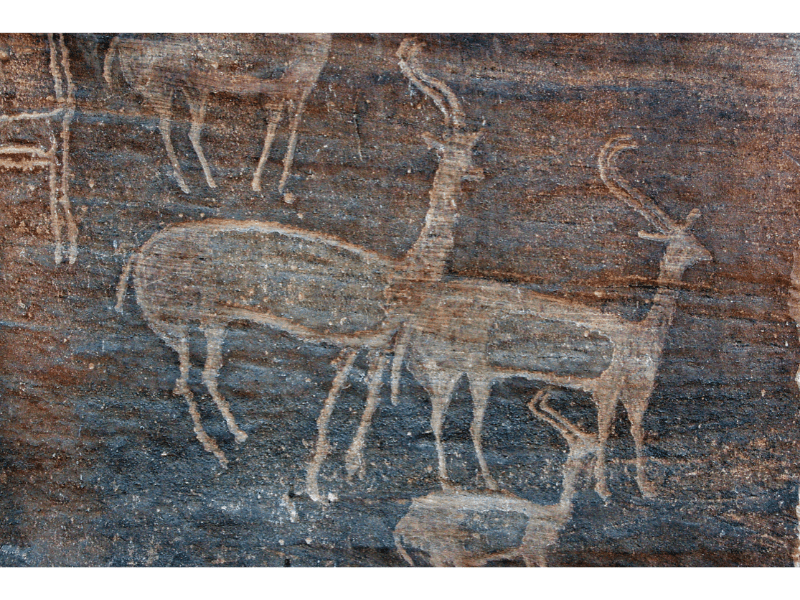

Since time immemorial, Egypt’s human history has centred around the River Nile and the annual floods that make its banks and delta so fertile. Archaeological evidence (including artefacts and rock carvings) show that the Nile Valley was inhabited by our ancestors as early as the Pleistocene era – an epoch that ended approximately 11,700 years ago. Originally these people were seasonal visitors; nomadic hunter-gatherers who took advantage of the Nile region’s plentiful flora and fauna.

However, climate change gradually led to the expansion of the Sahara Desert, and these hunter-gatherers were forced to adopt a more sedentary lifestyle. By the 6th millennium BC, permanent settlements had begun to appear on the river banks and their residents had learned how to clear and irrigate the land – and how to raise crops and livestock to ensure their survival all year round. Egypt saw the emergence of several different cultures from 5500 BC onwards. Artefacts from this period show increasingly developed pottery techniques and suggest that trade relationships were established between Upper and Lower Egypt, the Sinai Peninsula and Nubia.

The culture that immediately preceded the dawn of Dynastic Egypt was known as Gerzeh, or Naqada II. During this time agricultural techniques became so advanced that an entirely sedentary lifestyle was possible, and settlements grew in size so that the largest cities had over 5,000 residents. Many elements of Early Dynastic Egypt began to emerge at this time, including the use of adobe in building projects, the use of copper to fashion tools and weapons instead of stone, and the ornamental use of luxury materials including silver and gold.

The Early Dynastic Period

Traditional chronology dictates that in approximately 3150 BC, the pharaoh Menes unified Upper and Lower Egypt and in doing so became the founder of Egypt’s First Dynasty. Later archaeological evidence suggests an alternative version of events, in which the final king of the Gerzeh period, Narmer, unified Egypt. Discrepancies regarding dates and names of the early pharaohs are common, mostly because the evidence available to us is either incomplete or open to interpretation.

Either way, the Early Dynastic Period laid the foundations for the glorious pharoaonic eras to follow – quite literally. These early pharaohs were buried beneath rectangular, flat-topped tomb markers known as mastabas, which would eventually become the prototype for the first step pyramid and later for the smooth-sided pyramids for which Ancient Egypt is now so famous.

The Old Kingdom

The period of Dynastic Egypt that lasted from the Third Dynasty to the Sixth Dynasty (circa 2686 to 2181 BC) is known as the Old Kingdom. The pharaohs of the Old Kingdom chose Memphis as their capital and it was here that Third Dynasty pharaoh Djoser commissioned the first-ever pyramid. This stepped structure, known as the Pyramid of Djoser, still stands some 4,700 years later at the Memphis necropolis of Saqqara. A flair for architectural innovation defined the Old Kingdom, and it was during the Fourth Dynasty that the most famous pyramids of all were built. The Pyramids of Giza were built for the pharaohs Khufu, Khafre and Menkaure respectively, and Khufu’s Great Pyramid is the only one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World still standing today.

During the Old Kingdom, pharaohs became so powerful that they assumed sole rulership of the previously independent Egyptian states that would thereafter become known as nomes. The pharaoh was worshipped as a deity, and believed to be directly responsible for the life-giving annual flood of the River Nile.

Foreign trade expanded during this era, with sea routes established to Syria and the Horn of Africa bringing immense wealth to the kingdom. However, by the time of the Sixth Dynasty, stability in Egypt was undermined by increasingly ambitious regional governors, or nomarchs, and civil war erupted following the death of long-lived pharaoh Pepi II. The effects of an unclear line of succession were exacerbated by a major climatic event that resulted in years of low flood levels, and a famine that ultimately led to the collapse of the Old Kingdom.

First Intermediate Period

From the end of the Sixth Dynasty into the Eleventh Dynasty, Egypt was plunged into a 200-year period of instability known as the First Intermediate Period. This time is not particularly well documented, as the country was ruled by a series of nomarchs-turned-pharaoh who had little influence outside of their home province. The grand pyramids of the Old Kingdom were heavily looted, and eventually Egypt was divided once more into Upper and Lower Egypt. Two rival dynasties ruled each half of the country: one from Heracleopolis Magna in Lower Egypt, and one from Thebes in Upper Egypt.

Middle Kingdom

In 2055 BC, conflict between the two dynasties came to a head when the Theban pharaoh, Mentuhotep II defeated his rival and reunified the country. In doing so, he became the first pharaoh of the Middle Kingdom, which would last from the middle of the Eleventh Dynasty into the beginning of the Thirteenth Dynasty. The Middle Kingdom was characterised by a series of military campaigns, many of them aimed at reclaiming Nubia (which had gained independence during the First Intermediate Period). The rulers of the Eleventh Dynasty maintained Thebes as their capital, but the first of the Twelfth Dynasty pharaohs, Amenemhat I, moved the centre of power to Itjtawy, near present-day Lisht.

Stability reigned in Egypt until the rule of Amenemhat III, when a rapidly expanding population and failed Nile floods combined to create another period of famine. Feelings of discontent and unrest were exacerbated by Amenemhat’s decision to invite settlers from the Levant to Egypt to work on his monumental building projects. The Thirteenth Dynasty gradually declined into another era of uncertainty known as the Second Intermediate Period.

Second Intermediate Period

During the Second Intermediate Period, the weakened monarchy was unable to prevent the establishment of a rival Fourteenth Dynasty based out of Avaris. In 1650 BC, a Levantine people known as the Hyskos successfully invaded Avaris and later Memphis, seizing control of Egypt and establishing their own Fifteenth Dynasty. In response, the native Egyptian rulers of Thebes claimed independence and set up the Sixteenth Dynasty, which continued to stand against the Hyskos with varying degrees of success until eventually the Seventeenth Dynasty pharaohs managed to drive the Hyskos back into Asia.

The New Kingdom

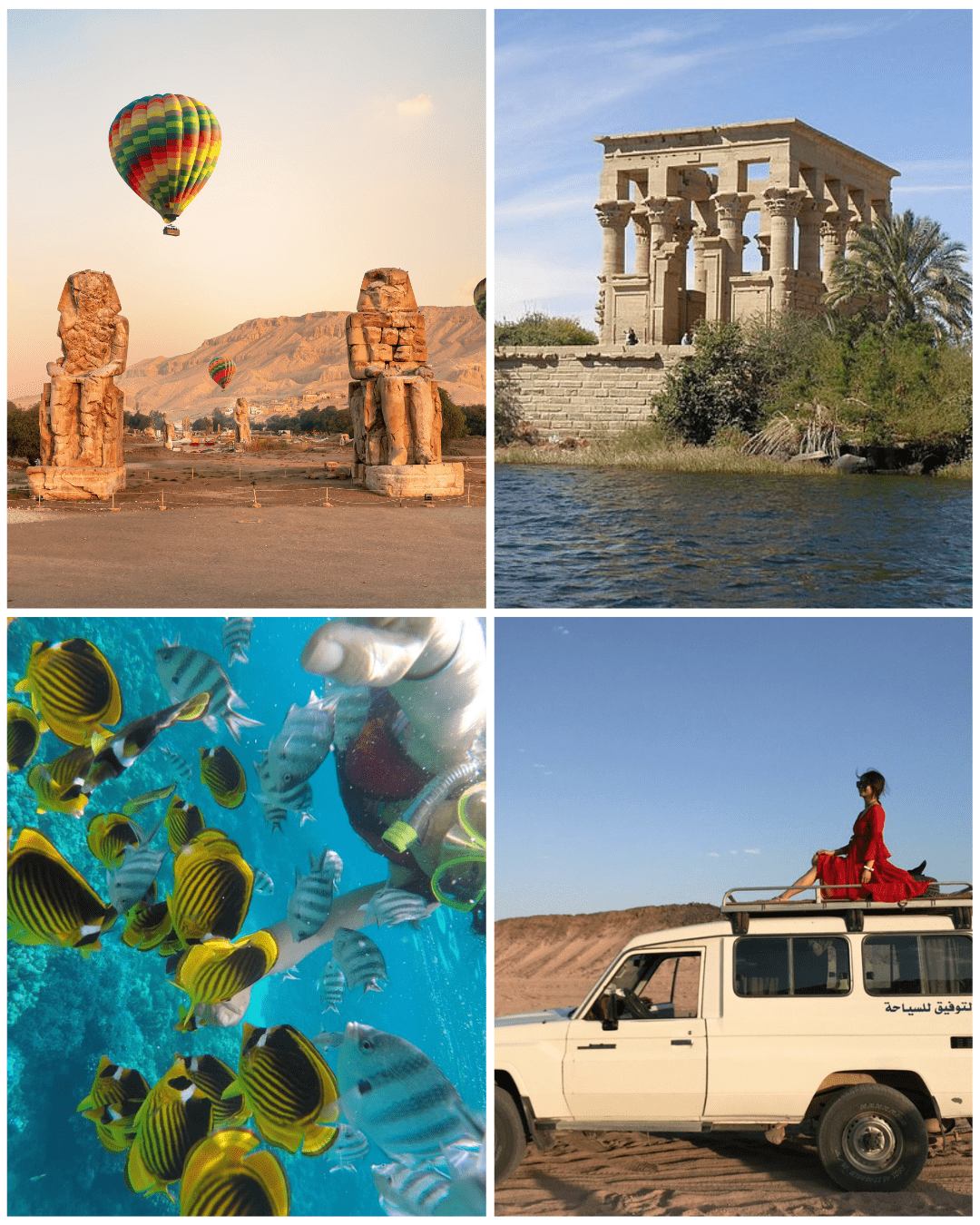

Ahmose I was the next great Egyptian pharaoh. With the restoration of Theban rule over a unified Egypt and the territories of Nubia and the Southern Levant, he became the first pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty and the New Kingdom – a period marked by incredible wealth and power. The New Kingdom yielded some of Ancient Egypt’s most iconic pharaohs, who were in turn responsible for many of the monuments that still stand along the banks of the River Nile today. Their military campaigns increased the territory of Ancient Egypt to its greatest extent, with significant victories in Nubia and the Near East.

The Eighteenth Dynasty in particular is defined by famous rulers including the female pharaoh Hatshepsut, Thutmose III, Amenhotep III and Amenhotep IV. The latter is best remembered for changing his name to Akhenaten in honour of the sun god, Aten, and abandoning the rest of the Egyptian pantheon in order to worship Aten exclusively in what is often regarded as the world’s first example of monotheism. Akhenaten’s religious beliefs were deeply unpopular both with the general Egyptian populace and his successors. Later pharaohs, including the famous boy-king Tutankhamun, dedicated their reign to reinstating the traditional gods and goddesses.

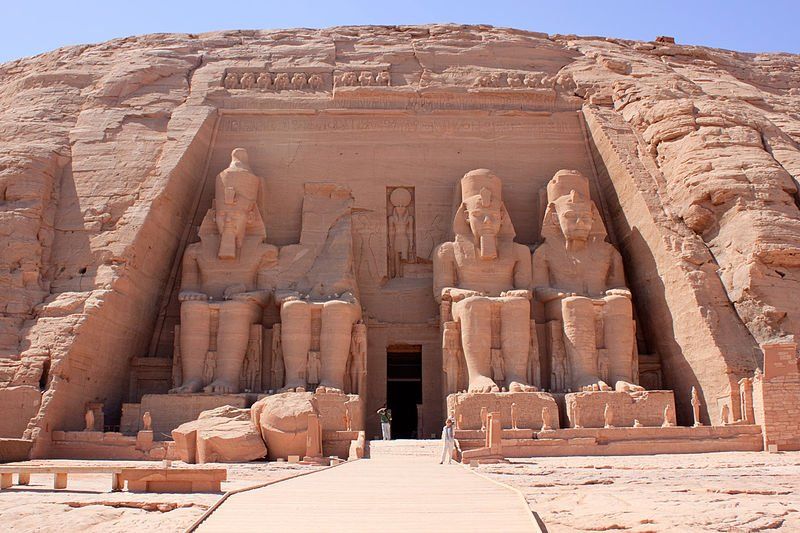

The last Eighteenth Dynasty pharaoh, Horemheb, died without producing an heir and appointed Ramesses I as his successor instead. Ramesses I’s descendant, Ramesses II, is often hailed as the greatest and most influential pharaoh of all time, and his many successful military campaigns are commemorated in the reliefs of temples like those at Abu Simbel. Despite Ramesses II’s glittering legacy, the cost of maintaining the expanded empire led to the depletion of the treasury by the reign of Ramesses III. Food supplies dwindled, and the Twentieth Dynasty descended into a series of brief reigns, drought, famine and social unrest.

Third Intermediate Period

By the beginning of the Third Intermediate Period, Egypt was once again divided with the founder of the Twenty-First Dynasty, Smendes, ruling out of Tanis and the High Priests of Amun ruling from Thebes. The next 400 years saw Egypt reunited and divided again several times, with nomarchs gaining influence and foreigners from Libya and Nubia seizing power where they could. The dynasties of this period are poorly documented, and often ran concurrently; and by 700 BC, Egypt was increasingly viewed as being under threat from the kingdom of Assyria. Conflicts between Assyria and Egypt became commonplace. In 671 BC, Memphis was sacked by the Assyrian ruler Esarhaddon. He established the Saite Dynasty, whose pharaohs were supposedly loyal to Assyria but later threw off all ties with the Assyrians and ruled a reunited Egypt for another century and a half.

Persian and Macedonian Rule

With the sixth century BC came another great power: the Achaemenid Persian Empire. In 525 BC the Persian king Cambyses II invaded Egypt and established himself as pharaoh. Egypt was run as a Persian province, or satrapy, until 404 BC when its people revolted under Amyrtaeus and succeeded in regaining independence. Amyrtaeus became the first and only pharaoh of the Twenty-Eighth Dynasty, paving the way for the Twenty-Ninth and Thirtieth Dynasties until the Persian king Artaxerxes III reconquered Egypt in 343 BC. Nectanebo II was the last ruler of the Thirtieth Dynasty, and the last native ruler of Ancient Egypt.

In 332 BC, control of Achaemenid Egypt was handed over to the Macedonian king, Alexander the Great, without conflict. After so many years of Persian subjugation, Alexander was hailed as a saviour by the Egyptians – especially after the oracle at Siwa Oasis proclaimed him to be the son of Amun, Thebes’ patron deity. Although respectful of Egyptian customs and religion, Alexander effectively turned Egypt into a Hellenistic state by establishing a new capital at Alexandria and appointing Greeks to the country’s most important positions. He used the wealth generated by the fertile Nile Valley to support his continuing campaign against the Persians.

The Ptolemaic Dynasty

When Alexander died in 323 BC, civil wars erupted across much of his empire as his generals and heirs fought for control of each state. Egypt was no different, and the succession struggle eventually resulted in the accession of Ptolemy (a close companion of Alexander) to power. Having established himself as Egypt’s new ruler, Ptolemy took on the title of pharaoh in 305 BC and founded the Ptolemaic Dynasty, which would last for nearly three centuries. The Ptolemies adopted the customs, religion and dress of the native Egyptian pharaohs and were generally accepted as their successors.

The dynasty ended with female pharaoh, Cleopatra VII. Renowned for her tumultuous family relationships, her affairs with Julius Caesar and Mark Antony, and her role in the transition of the Roman Republic into the autocratic Roman Empire, Cleopatra has become one of the most iconic figures of Ancient Egyptian history. After Octavian defeated Mark Antony in 30 BC, both Antony and Cleopatra committed suicide – leaving Egypt to become an annexe of the Roman Empire and the Ancient Egyptian era to finally draw to a close.